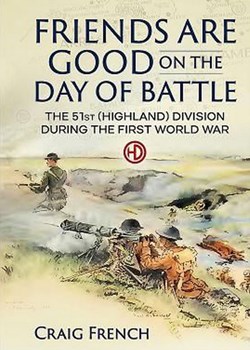

After the hardcover print run for ‘Friends Are Good On The Day Of Battle’, there is now an electronic version available at Helion and Company.

The aim of this book is to evaluate the 51st (Highland) Division over the course of the First World War. Underpinning the study is an analysis of both change and continuity – at home and overseas – and the performance of the division as a fighting unit. The key themes identified for study have been training, esprit de corps, recruitment and reinforcement, and battle performance. Through the investigation of the key themes, other important characteristics have been analysed, such as command and control, organisation, and the level of centralisation in both the formation and in the wider army.

Key questions in the research apply to both divisional study and to wider academic understanding of the First World War. The book considers a number of themes that have been neglected by historians old and new, and brings into sharp focus some areas of research that may have produced inaccurate assumptions. In addition, a substantial range and quantity of primary sources have been utilised – many unexplored until now. The selection of the 51st (Highland) Division for study was based on a number of criteria: (Highland) Division experiences were both unique and not unique. In some areas, it was a very individual formation, but in other areas (or at particular times of the war), it was not.

The following quotations give some indication of the depth and variety of sources, and the distinctive nature of the 51st: From J.F.C. Fuller, Memoirs of an Unconventional Soldier: ‘Presently a section of the night seemed to be advancing slowly towards us, an undistinguishable mass in the darkness; they came on at a pace which was just on the active side of standing still. As they passed, we learned that they were a Highland battalion, part of the 51st Division that fought so well and suffered so heavily on the following day. None of them spoke, and their silence, the weight and slowness of their tread, and the solemnity of their passing by, bore such an implication of fate, and were shrouded with so much mystery by the night, that one felt as if one were hailing men no longer of this world’.

Major-General D.N. Wimberley: ‘These two opposing characters of two different types of Scots, the fire of the Highlander and the dourness of the man from the Plains, were so blended in the old Highland Division that come what might against us the Division was resolute’.

From M.M. Haldane, A History of the Fourth Battalion The Seaforth Highlanders: ‘Long after the war was over a distinguished Irish General expressed the hope that if ever he had troops under him again they might be Scots. A Scotsman present expressed surprise at his preference for foreigners, to which the General replied that he held that hope because of the high standard of Scottish education, which ensured that the youngest lance-corporal would intelligently carry on his Commander’s intentions even after all his officers were killed’.

From J.G. Fuller, Troop Morale and Popular Culture in the British and Dominion Armies 1914-1918: ‘The 51st perhaps owed its pre-eminence among Scottish Divisions in part to the fact that it was, until April 1918, the only Scottish Territorial Division on the Western Front: the 52nd (Lowland) was lost in the comparative backwater of the Palestine theatre. That left only the 9th and 15th Divisions which, as Kitchener formations, could not of course match the 51st’.

Undoubtedly, the 51st (Highland) Division left strong impressions. How accurate were these impressions? Were they a result of something more than just consistent fighting quality? Indeed, was there a consistent fighting quality?

“For any fans of this division or with interest in the “learning curve”, a good addition to your library.” Long Long Trail website

“this is an extremely impressive piece of work……Wholeheartedly recommended, whether or not you are a Scotsman!” SOFNAM

“…..written in an easily read style…..French provides a more pragmatic assessment and deeper insights into the training, composition, and character of the 51st (Highland) Division than other histories have done, and along the way he challenges some long held views.” Chris Roberts, Land Power Forum, Australian Army Research Centre